Zohran Mamdani’s meteoric rise to become the front-runner in the New York City mayor’s race was fueled by his promise to make the city more affordable. He has highlighted four signature policy proposals: universal child care, free buses, city-owned grocery stores and a rent freeze on rent-stabilized apartments.

These ideas have excited New Yorkers who are worried about the soaring cost of living. But if Mr. Mamdani wins, the plans could be difficult to implement.

He would have to secure support from critical stakeholders, find funding to pay for the plans and hire the right staff members to make sure they are successful.

Free child care for every child under the age of 5 is the most ambitious idea — and the most expensive.

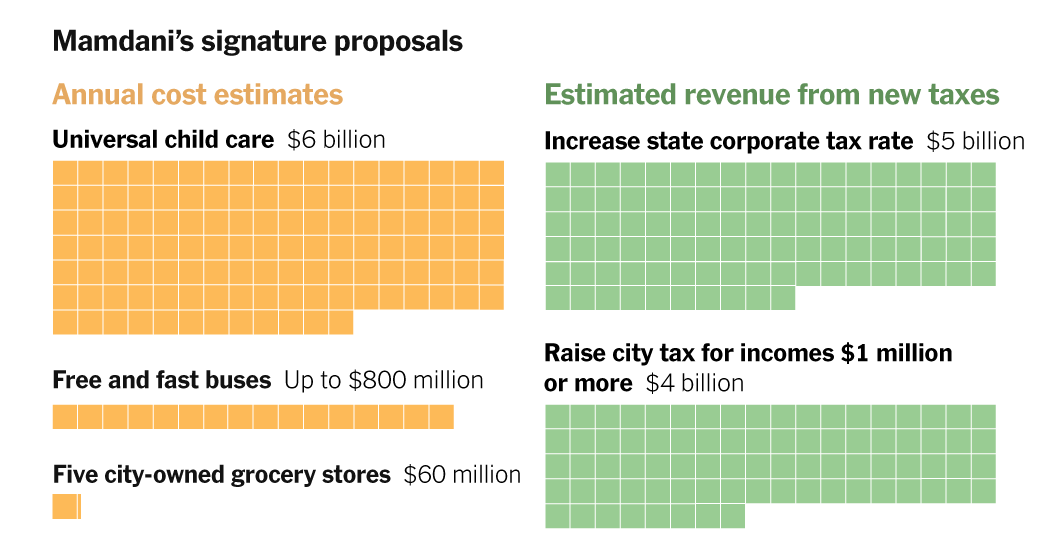

All together, the policies could cost nearly $7 billion every year. If all of them were implemented, the cost would be higher than the Police Department’s budget.

But New York City has the largest budget of any city in the country at nearly $116 billion. Mr. Mamdani has argued that there is room within it to spend more on his priorities.

Mr. Mamdani has given broad cost estimates for each of his four proposals. But his campaign has not provided a detailed breakdown.

His two opponents in the mayor’s race – former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo, who is running as an independent, and Curtis Sliwa, the Republican candidate – have offered their own affordability plans and criticized Mr. Mamdani’s limited experience in government. Mr. Cuomo proposed his own plan for free buses, but only for low-income New Yorkers.

How would he pay for the four plans?

Mr. Mamdani wants to raise $9 billion dollars in new revenue by increasing income taxes for wealthy residents and corporate taxes on businesses — a contentious proposal that would require support from state lawmakers.

He also wants to streamline city contracts, hire more auditors to enforce the tax code and collect more fines — three measures that he says could raise an additional $1 billion per year. These changes would most likely need support from the City Council as part of the budget process.

If the costs of his plans end up on the higher range of estimates, the new revenue might not cover the full cost. Gov. Kathy Hochul, a moderate Democrat who recently endorsed Mr. Mamdani, opposes raising taxes. But Carl Heastie and Andrea Stewart-Cousins, the Democratic leaders of the State Assembly and Senate, who also endorsed Mr. Mamdani, have previously backed tax increases on the wealthy.

Mr. Mamdani wants to raise taxes on New Yorkers who earn $1 million per year or more by two percentage points. For example, someone who earns $1 million would pay an additional $20,000 in city income tax.

He wants to raise the top corporate tax rate to 11.5 percent from 7.25 percent, in order to match New Jersey’s rate. His critics say that the city already has high tax rates and that these changes could prompt wealthy residents and businesses to leave.

Mr. Mamdani has said that he is open to other funding streams as long as his policy goals are achieved. He said in a recent interview that there was room within the city budget and the $250 billion state budget to take “steps toward fulfilling this agenda.”

Mamdani’s proposals

Universal child care

The biggest plan, by far, is free universal child care. The city already offers free preschool for all 4-year-olds and many 3-year-olds. Expanding child care to infants and to toddlers under 3 would be a major challenge. Mr. Mamdani’s administration would have to create new day care facilities and hire scores of child care workers.

How much would it cost?

The Mamdani campaign estimates that this could cost $6 billion annually.

Universal child care

$6 billion

Who has to approve the policy?

New York State. Mr. Mamdani wants to pay for the program by raising the state’s corporate tax rate and increasing the city’s income tax. Any tax increases would need approval from the state.

What do experts say?

Cost estimates vary widely, and it is possible that Mr. Mamdani might embrace a phase-in approach starting with older children or low-income families first, instead of expanding child care to all families at once.

The Fiscal Policy Institute, a left-leaning policy group, estimated that, using current wage levels, implementing universal child care would cost $2.5 billion per year in New York City.

New Yorkers United for Child Care, an advocacy group, said that it would cost $12.7 billion for the entire state, or 6 percent of the state budget. The cost of a statewide program has been studied more closely; many experts believe that universal child care should be implemented at the regional or national level.

Estimates for child care programs vary widely depending on enrollment rates and the wage levels of the child care workers. The average annual salary of a child care worker in New York State is $38,000. Advocates say that it should be closer to $85,000, the average for a kindergarten teacher.

Experts agree that implementing the plan would be a monumental task. Lauren Melodia, the director of economic and fiscal policy at the Center for New York City Affairs at the New School, who is studying the costs, said that the city needs more child care workers, that it is a labor-intensive industry and that many workers are currently underpaid.

But experts also agree that it would have economic benefits for the city and for mothers in particular. A recent report from the city comptroller found that it would bring 14,000 mothers to the work force, generating $900 million in labor income.

Fast and free buses

Mr. Mamdani has pledged to make city buses fast and free. More than one million people take the bus every day, and the system is used primarily by working-class New Yorkers. The buses are notoriously the slowest in the country and inch along at an average of eight miles per hour.

How much would it cost?

The campaign says this will cost less than $800 million annually. Last year, there were nearly 410 million bus trips. At a cost of $2.90 per fare, and factoring in 2024’s fare evasion rate of 48 percent among bus riders, it would cost more than $600 million to make buses free.

Fast and free buses

Up to $800 million

The cost could fluctuate depending on how many people take the bus. In 2019, a year when ridership was higher before the pandemic changed commuting habits, making buses free would have meant covering $900 million in bus fares.

Mr. Mamdani also wants to speed up buses and build more bus lanes, including busways that prioritize buses over cars. For example, a route on 14th Street in Manhattan that bars almost all through traffic except for buses and commercial trucks has been popular.

Who has to approve the policy?

New York State. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, a state-run agency, operates the bus network. Mr. Mamdani would have to negotiate with Ms. Hochul and state lawmakers.

As a State Assembly member, Mr. Mamdani sponsored a free bus pilot program. Five lines, one in each borough, were made free for a year. Ridership increased by nearly a third on weekdays, but bus speeds did not increase.

What do experts say?

A report by Charles Komanoff, a transportation economist, indicated that making buses free would speed them up by 12 percent because of faster boarding times. The Independent Budget Office did another estimate using ridership data from 2022 that put the annual cost at $652 million.

City-owned grocery stores

Mr. Mamdani wants to test out the idea of city-owned supermarkets in the hopes of bringing down grocery prices. He would create one in each borough as part of a pilot program and then consider expanding the program if successful.

How much would it cost?

It could cost roughly $60 million annually to open five grocery stores. The city would most likely cover the cost of rent, utilities and property taxes, and the stores could buy and sell goods at wholesale prices and use central warehouses. Chicago explored the idea and found that the upfront costs of creating three stores was about $26 million.

City-owned grocery store pilot program

$60 million

Who has to approve the policy?

The city. The pilot program is not as costly as the other proposals and it could be included in the city budget, which the mayor negotiates with the City Council.

What do experts say?

An alternative estimate by food policy experts published on the website Civil Eats indicated that the policy could be more expensive, in the range of $100 million, assuming union labor rates and free rent.

| Mamdani’s campaign | 5 city-owned grocery stores | $60 million |

| Civil Eats | 5 city-owned grocery stores | $100 million |

| Civil Eats | Network of 20 stores | $400 million |

If the pilot program were to be successful, the city could expand it. Having 20 stores that use a bulk warehouse model like Costco’s could cost $400 million annually, according to the report published by Civil Eats.

Alexina Cather, the director of policy at Wellness in the Schools, a nonprofit that shapes food policy, said that grocery stores typically have small profit margins, but that if the city adopted the model proposed by the Civil Eats report, it could significantly reduce operating costs.

Rent freeze

The rent freeze proposal for the city’s nearly one million rent-stabilized apartments could be the easiest to achieve.

How much would it cost?

No direct cost to the city budget.

Who has to approve the policy?

The Rent Guidelines Board, which has nine members who are appointed by the mayor.

What do experts say?

The board approved rent freezes for three years under Mayor Bill de Blasio, who argued that they were necessary to help struggling renters. Mr. Mamdani could appoint people to the board who are ideologically aligned with him, though members have staggered terms, and he might not be able to overhaul the board all at once.

Keeping rents at their current levels would not require new spending by the city. But it could require building owners to shoulder more costs, including maintenance for older buildings and property taxes.

Critics of the plan have also raised concerns that a rent freeze alone would not address soaring rents for market-rate units and the urgent need to build more affordable housing quickly. Mr. Mamdani has a separate plan focused on building 200,000 affordable units over the next decade.

Since winning the Democratic primary in June, Mr. Mamdani has worked to expand his coalition and build relationships to implement his ideas. If he wins, many New Yorkers will be watching closely to see if he delivers.