Back in 2021, when Andrew M. Cuomo’s governorship was in free fall, the real estate developer Jeff Gural was clear about what he thought of the man: “He’s smart, but he’s a bully, and his tactics are a disgrace.”

Representative Ritchie Torres took a graver tone against Mr. Cuomo, declaring that New York was “no longer governable under his leadership” amid mounting sexual harassment claims.

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, a leading exponent of women’s rights, called the accusations “deeply, deeply troubling.” The remarks were part of a Democratic pile-on that helped force a reluctant Mr. Cuomo to resign.

How quickly things can change.

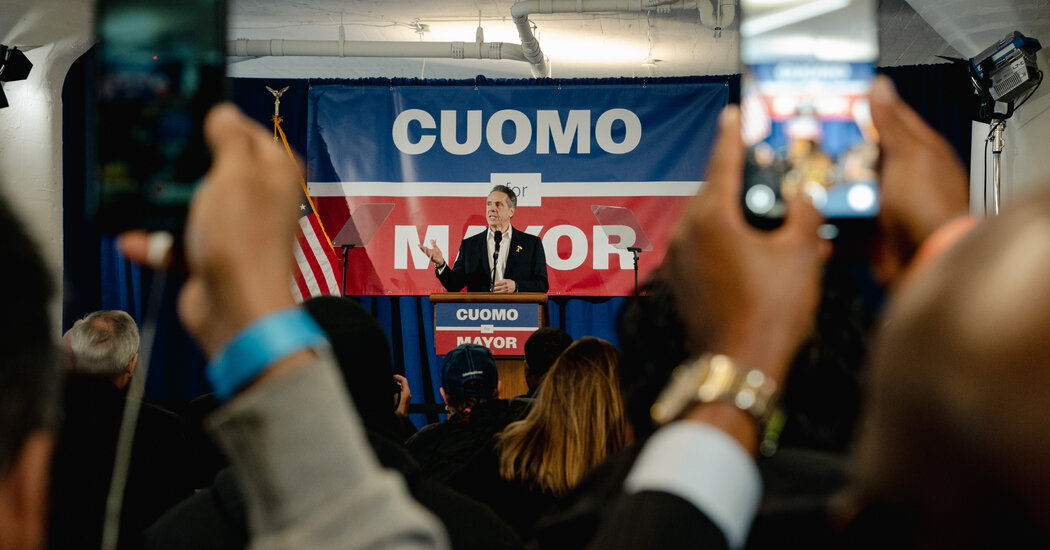

Not quite four years later, as Mr. Cuomo attempts a comeback as a candidate for mayor of New York City, the state’s powerful Democratic establishment now appears more interested in getting back in his good graces than in stopping him.

It is a striking about-face that may prove to be a defining feature of June’s Democratic primary. The born-again Cuomo supporters include elected officials, business titans and labor unions whose collective influence could push Mr. Cuomo to victory — whiplash be damned.

Mr. Gural recently donated $2,100 to Mr. Cuomo’s campaign. Mr. Torres gave his blessing to “the resurrection of Andrew Cuomo” before he even entered the race. Representative Gregory W. Meeks, the Queens Democratic chairman, gave Mr. Cuomo the nod with little mention of his past criticism.

Powerful interest groups that helped end his governorship, like the Real Estate Board of New York and the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council, are seriously considering following suit. Even Ms. Gillibrand made clear she does not intend to stand in the way.

“This is a country that believes in second chances,” she recently told NY1. “So it’s up to New York voters to decide if he should get a second chance to serve.”

The spate of election-season conversions undoubtedly reflects a broader cultural shift that has led voters and power brokers alike to reconsider the case of Mr. Cuomo, who denies wrongdoing. Others say that the threat posed by Washington, or the left, is too grave to elect anyone less experienced.

But privately, prominent New Yorkers are also engaging in far more transactional calculations. Many still loathe Mr. Cuomo. But they take notice of his polling lead and privately reason it is best not to be on the bad side of a notoriously vengeful leader who could have sway over zoning rules, labor contracts and more.

“Right now, the way the game is being played politically is that when you look to other people, you assess how their fortunes affect you,” said former Gov. David A. Paterson. “That is a display of power — not necessarily righteousness, not necessarily fairness.”

He added, “It really looks hypocritical.”

Mr. Paterson, who has remained neutral, compared it with the dynamic around President Trump, who managed to win back not only his voters but Republican leaders who tried to push him aside after the riot at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

There are notable holdouts. Eight Democrats are running against Mr. Cuomo in the primary, and Mayor Eric Adams remains in the race as an independent. They have support from politicians and civic leaders who say they cannot stomach Mr. Cuomo’s return.

A group of high-ranking Democrats, including the state attorney general, Letitia James, were so alarmed by a potential Cuomo return that they quietly tried to recruit a formidable moderate who could beat him. Ms. James even briefly considered doing it herself, but like the others, she passed and has largely restrained from attacking.

Gov. Kathy Hochul, who took office when Mr. Cuomo resigned in 2021, recently told reporters that she stood by her comments at the time, calling his actions “repulsive.” But, she concluded, “I have to deal with the reality today.”

Several prominent civic and political leaders were unwilling to criticize Mr. Cuomo on the record, citing his penchant for holding grudges and acting on them. One acknowledged having done everything possible to try to undermine him — and failing.

All of it has left allies of the women whose accusations ended Mr. Cuomo’s governorship feeling betrayed and worried he could do damage if elected.

“The politicians who support him now will be responsible for the damage,” said Mariann Wang, a lawyer for Brittany Commisso, who accused Mr. Cuomo of groping her while she worked in his office. “They can’t say they weren’t warned.”

Mr. Cuomo denied harassing Ms. Commisso; the Albany sheriff’s office filed a criminal complaint, but prosecutors dropped the case.

His return has been years in the making. He spent millions of dollars in taxpayer funds fighting to defang the sexual harassment claims and investigations related to his Covid-era policies. He assiduously courted former critics.

Rich Azzopardi, a spokesman for Mr. Cuomo, said no one should be surprised by the groundswell of support for the former governor. He called him “the only person in this race with the proven track record of results to tackle” the city’s problems. He argued that time had allowed for “clarifying due process” for Mr. Cuomo to defend himself.

“Since the beginning, we said all of this was political and wasn’t going anywhere,” he said. “Four years later, that has all borne out.”

Some have been less receptive than others. Mr. Cuomo has been pushing, without luck, for a private meeting with Rupert Murdoch, the owner of The New York Post, to try to smooth a rocky relationship with the conservative tabloid, according to two people familiar with the discussions. The Post has hammered Mr. Cuomo daily.

Others are open-minded. Assemblyman Ron Kim was so disgusted by Mr. Cuomo’s attempt to conceal Covid-related deaths in nursing homes that he led a drive to impeach him. Their war of words — Mr. Kim said Mr. Cuomo threatened to “destroy” him — once consumed Albany.

But Mr. Kim now says he is willing to reconsider. “I’ve always been open to giving people a fair shot,” he said. “I want to see sitting across from him if he’s changed.”

Mr. Cuomo has also benefited from larger social and political shifts.

Laura Curran, the former Nassau County executive, said she felt tremendous pressure when claims against the governor first surfaced in spring 2021 “to jump on the bandwagon and do it fast.”

But after no legal charges were brought against Mr. Cuomo, she now views the whole case as “a nothingburger” that says more about the “cancel culture” that gripped her party than the former governor. She recently co-hosted a Cuomo fund-raiser with other women, and said having “ a tough guy like Cuomo as the leader of New York City is a good thing” in the Trump era.

If anything, the bandwagon now appears to be pointed in the opposite direction.

“Any endorsement for him is predicated on a belief he’s going to win,” said John Samuelsen, whose Transport Workers Union has not taken sides. “It doesn’t have to be deeper than that to understand the rationale.”

Jay Jacobs, a former Cuomo ally who leads the New York Democratic Party, offered another theory: “Time cures a lot of stuff, and people’s memories are not as sharp,” he said. “That doesn’t make it right or wrong. That’s just the reality.”

Many have simply refused to discuss their transformations.

Mr. Torres told The Post that he was not interested in “relitigating” Mr. Cuomo’s resignation and did not respond to questions for this article. In any case, his early endorsement of Mr. Cuomo could prove useful if the congressman follows through on threats to run against Ms. Hochul in a primary next year.

Ms. Gillibrand’s carefully stated neutrality caught many Democrats by surprise, given her role helping to push Senator Al Franken of Minnesota from office in 2017 over allegations of unwanted touching and kissing. Her spokesman pointed to remarks in which she said it was up to voters to weigh Mr. Cuomo’s alleged misconduct against his accomplishments.

As for Mr. Gural, the real-estate developer, he said in an interview that he would have preferred Mr. Adams for another term. But he sounded ready to move past his attacks from 2021, when he told The Wall Street Journal that he donated to Mr. Cuomo because he felt pressure to. (The governor’s office said then that Mr. Gural was upset because his casinos had not gotten favorable treatment.)

“Andrew gets things done,” Mr. Gural said. “Everybody is looking at all the others as too left-wing.”

Benjamin Oreskes contributed reporting.